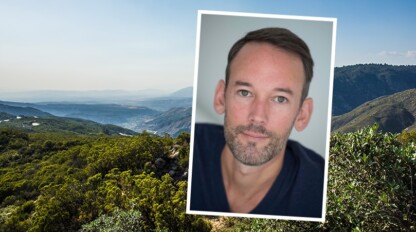

Felix & Paul Studios’ Emmy-winning The People’s House: Inside the White House with Barack and Michelle Obama suggests the potential of the Oculus virtual reality (VR) equipment that Neil Short uses. But Neil’s Virtual Reality Filmmaking course at Idyllwild Arts Academy makes the potential of VR 360-degree filmmaking explicit while also spelling out the challenges.

“It’s obviously a powerful way to give the viewers a sense of being right there as part of the action,” he says. “But by freeing viewers to look around you also sacrifice your ability to direct their attention.”

Think of the moment in 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road when Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) unleashes her primal scream. She’s just left of center on the screen and the desert landscape is almost featureless. Director George Miller and cinematographer John Seale knew that every viewer’s eyes would lock onto Theron.

But the landscape is beautiful. The rich color of the sand includes subtle variations in hue that pursue the viewer as the wind chases the sand toward the surface of the screen. Didn’t the sand look like that the first time you went to surf Redondo Beach?

In other words, there’s plenty to look at if the camera doesn’t aim you at Theron. But how does a filmmaker aim viewers who have control over their own gazes to look all around themselves?

“We appeal to your other senses,” Neil tells his interviewer, who’s slightly disoriented by having just tried on a VR headset for the first time. “Spatialized sound can draw the viewer’s attention to where the director wants it.”

In the Dark Ages

“So for a Dark Ages movie like Casablanca,” the interviewer says, “if 360 technology had been available but the director wanted you looking not at the hulking car off to the side, but at Bogart when he tells Ingrid Bergman ‘We’ll always have Paris’ . . .”

Neil smiles as the interviewer’s voice trails off.

“Go on,” he says.

Like any good teacher, Neil seeks a balance between giving his students information and prompting them to find it for themselves.

“Spatialized sound means making the sound come from different areas of what the viewer can see? You could make the strains of “As Time Goes By” swell up from the brim of Bogart’s fedora?”

“Got it,” Neil says, his smile broadening. “You’re ready to be one of my students.”

The interviewer appreciates the encouragement, but knows he isn’t ready.

“In addition to sound,” Neil continues, “we can direct a viewer’s attention through creative use of lighting and blocking, which is the actor’s movement. For example, if we want the viewer to know that a gunslinger has just walked into the saloon, we can have several characters turn to look at the door. It’s natural to want to know what other people are looking at and we are able to harness human nature to guide viewers through the story.”

Still Learning

During a thirty-minute chat the interviewer can absorb only a tiny fraction of what there is to learn about virtual reality filmmaking. It’s why Idyllwild Arts Academy offers the year-long class and why Neil himself says “I’m still learning.”

He adds that “immersive technology is advancing at an incredibly rapid pace, which requires constant research and experimentation.”

A grant from Arts Enterprise Laboratory funded purchase of the course’s Oculus hardware and software, as well as a February master class taught by VR sculptor CS Murphy. The Academy’s Film and Digital Media Department, for which Neil teaches, paid for its own Insta360 Pro 2 VR camera, Senhiser Ambio microphone, Zoom F8 & H2N recorders, and several Oculus Go headsets.

Of course, Neil’s love of storytelling brings alive the possibilities of that hardware and software for students.

His pursuit of an M.F.A. in Dramatic Writing from Savannah College of Art and Design, where he’s already earned an M.F.A. in Film and Television and an M.A. in Visual Effects, has made him keenly aware of another challenge for 360 filmmakers. Consider that it doesn’t have to be a bad thing if someone watching a 360-degree Mad Max or a 360-degree Casablanca wants to look away from Theron or Bogart.

“It’s like theatre in the round,” Neil says. “The screenwriter has to describe the action in six different zones: Up, Down, Front, Back, Left, and Right.”

This may or may not be six times as hard as traditional screenwriting. But if it is, Neil and his Idyllwild Arts Academy students will approach it not as an impossibility, but as an exciting challenge.