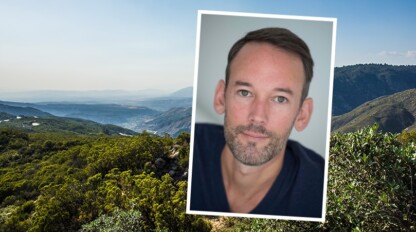

Pictured above: With Naiche, baby Mia, Nitanis, and Manaya a couple of years ago.

The high temperature in Idyllwild on Monday, March 1, was sixty-one degrees. In Edmonton the weather was warmer than you might have expected: forty-six, double the high of the previous day. But the province of Alberta stretches seven hundred and sixty miles from north to south, and Edmonton sits below the midway point. The weather would have been colder in northern Alberta.

The high temperature in Idyllwild on Monday, March 1, was sixty-one degrees. In Edmonton the weather was warmer than you might have expected: forty-six, double the high of the previous day. But the province of Alberta stretches seven hundred and sixty miles from north to south, and Edmonton sits below the midway point. The weather would have been colder in northern Alberta.

Violet Duncan was speaking from northern Alberta about the part that she and her husband would play in Idyllwild Arts Academy’s upcoming Art in Society Symposium, taking place on March 12. The Symposium’s theme was to be Art and Healing. Violet and Tony Duncan practice a number of restorative art forms known to many Native American and First Nations tribes. These include the Hoop Dance, in which Tony had recently won his sixth world title in the contest held annually at the Heard Museum, in Phoenix (but, this year, virtually).

Violet mentioned that she and her four children, ages four to eleven, were staying in her childhood home on Kehewin Cree Nation with her extended family. Yet even the Zoom connection that blurred her image while making her movements seem abrupt and discontinuous, like a bird’s, could not conceal her frequent smiles or silence her frequent laughter. She and the children were happy to be where Violet had been born, on her parents’ land. Her mother is Taino and her father is one of almost a hundred thousand Cree who live in Alberta.

Traveling Many Roads

After a few minutes, Violet began smiling even more: Tony had joined the Zoom call from Arizona. In Mesa the high temperature on March 1 was sixty-eight. He stood outdoors beneath a perfect blue sky.

“I grew up in Arizona, so you know how it is,” he said in explanation of his black leather jacket. “The temperature gets below eighty and we have to bundle up.”

Tony is referring to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, more than a hundred miles east of Phoenix. He is Apache and Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara.

“At our house in Mesa the children had their friends knocking on the door all the time,” Violet said. “It was hard to stay safe from the pandemic. Tony drives back and forth between Mesa and Alberta, but he’s always traveled more than me since we had children.”

As Tony, squinting from the sun, moved into the shade, Violet continued.

“But they’re just about old enough to do some travel with. So I think maybe Italy. . .”

“Italy might be my favorite place to perform,” Tony said. “But I also like Paris, and South America. . .”

“And Tokyo,” Violet said. “Which Manaya”—their oldest, the eleven-year-old—”would love because she’s started to teach herself Japanese. I’ll be in the kitchen and she’ll come in and say something I don’t understand and I’ll think, ‘Of course I don’t understand: it’s Japanese!'”

Having grown up eighteen hundred miles from one another, Violet and Tony met in a place that was distant from both Arizona and Alberta.

“My parents had a professional performing arts company, and so did Tony’s,” Violet said. “They would hit the festivals. One year when we were both in Miami, for the Miccosukee festival, we met. The festival ended and I went one direction with my parents and he went the other direction with his parents. But we kept in touch.”

“We were married about fourteen months later,” Tony smiled. “We celebrated our thirteenth anniversary on February 16. After getting married, we started our own company and began performing.”

Versatility as Artists

Meeting Tony had altered Violet’s plan to enter the medical field. She may have owed her devotion to caregiving to her parents, whose performing arts company had been involved in social justice theatre and in theatre workshops that addressed problems like suicide and substance abuse on reservations. Yet her experiences with her parents had also made her aware that “we need creative engagement to bring balance and healing to our lives,” the fact that inspired this year’s Art in Society Symposium.

The Duncans’ versatility as artists is astonishing. Tony plays the flute and Canyon Records has released five of his albums, including Purify. And Violet’s self-published children’s books have caught the eye of Random House. The publishing giant will bring out her next book about contemporary Native life in 2022.

But the Art in Society Symposium was not designed to accommodate the full scope of Tony and Violet’s artistry. They were asked to talk about and perform the Hoop Dance, which, the Heard Museum explains, “multiple Indigenous communities” first used “as a healing ceremony.”

The healing is connected to the hoop’s circularity, hence its representation of the cycles that define the seasons and other natural processes. The Taos Pueblo people, according to Tony the originators of the Hoop Dance, and other Indigenous practitioners seek healing in a restoration of balance with nature.

The audience for Idyllwild Arts Academy’s Art in Society Symposium on March 12 was fortunate to be introduced to Violet and Tony Duncan and to see them demonstrate that balance.